Helen Tope has written a review of current exhibition Present Moments and Passing Time from artist Malcolm Le Grice. This exhibition is free to visit and open to all from 20th January to 18th March, here at the Plymouth Art Centre galleries.

Showing at Peninsula Arts and Plymouth Arts Centre, Present Moments and Passing Time is a large, ambitious retrospective, detailing the work of pioneering film-maker, Malcolm Le Grice.

Born in Plymouth, Le Grice moved to London after graduating from the Slade School of Fine Art, becoming one of the founding members of The London Film Co-operative in 1968. A group that encouraged the making, screening and distribution of experimental film, rather than outright ownership, Le Grice’s philosophy proved to be years ahead of its time.

Le Grice originally began his career in painting, but began to explore film-making by the mid 1960’s. Malcolm’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Louvre and Tate Modern. He has not only been influential during the post-war period, but continues to provoke and challenge, with Le Grice’s Castle 1 (1966) a clear influence on Martin Creed’s Turner Prize-winning Work 227 (2000).

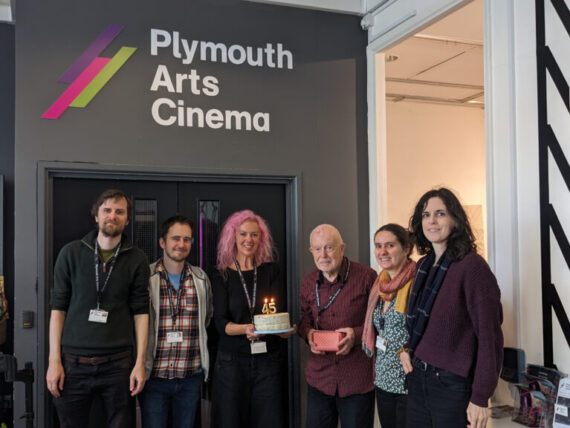

Exhibition: Malcolm Le Grice Exhibition

Plymouth Arts Centre Gallery, Lloyd Russell

In Present Moments and Passing Time, Plymouth pays tribute to Le Grice, with a city-wide celebration of his life and work. Working across several mediums, Le Grice avoids easy categorisation. Unsurprisingly, this exhibition features everything from feature length films to charcoal sketches. Le Grice’s career, as the exhibition title suggests, muses on the effects of time; how time can transform and erode memories, art, opinions and reputations. The Le Grice landscape is concerned with the transitory nature of it all. But what is found in this exhibition is not a dry treatise. Le Grice’s art buzzes with an electric force that is eternally youthful. It questions, but is not afraid to feel.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Le Grice’s film Little Dog for Roger (1967). The film short is based on fragments of a home movie, found by Le Grice in the 1960’s. Fragments of film are spliced together, with gaps in the film allowed to show through. Sprocket holes whizz across the screen; a narrative interrupted.

The film shows Le Grice’s family during a day out at Hexworthy, Dartmoor. The family dog is the centre of attention, bounding energetically across the moorland. Despite the age of the film, the subject matter captures something immediate and familiar.

Le Grice experiments with the film, by going beyond the immediate source material. The nostalgic feel is dislocated by Le Grice, who adopts a multi-projection technique, so we see several versions of the dog at the same time. It is a play on the elusiveness of memories, even when captured and laid down on film. The ‘truth’ – such as it is – gets overlaid with half-remembered fragments, things we believe to have happened. The dog appears in several realities, and each is as true / untrue as the other.

Le Grice resits chronology, both technically and thematically. Little Dog for Roger strides across the years to meet us; it is a subject both of and beyond its time. The screen lends an illusion of immortality, but Le Grice reminds us that even film, the observer and recorder, is built on moments, passing, present and gone.

Exhibition: Malcolm Le Grice Exhibition

Plymouth Arts Centre Gallery, Lloyd Russell

The exhibition takes advantage of Le Grice’s extensive back catalogue, showing several of his short films. Some just a few minutes long, they offer an insight not only into Le Grice’s process, but the ideas that have preoccupied him over the years.

In DENISINED – SINEDENIS (2006), we see a triptych of a man’s face; three views of the same subject. As the film begins, the soundtrack makes its presence felt. Featuring JS Bach’s Crab Canon from a collection of canons and fugues called The Musical Offering, the crab canon is a musical device that features two musical lines that are complementary and backward; a musical equivalent of the palindrome. The dizzying baroque soundtrack uses the same motif over and over again to produce a layered effect, mirroring what is happening on screen, as one image of the man projects itself onto the previous one. The triptych, at first sharply defined, begins to blur as we are presented with kaleidoscopic viewpoints of the subject. Pinning down a definitive image becomes impossible, with Le Grice creating a film that dances to the rhythm of Bach’s tune.

Le Grice’s reputation as an innovator is coupled with a strong connection to art history. References abound in this exhibition, not hidden away for the viewer to discover, but there on display for all to see. The work and legacy of Leonardo Da Vinci, Andy Warhol and Edouard Manet is explored in After Leonardo (installation 1974-2015; collage 1993); After Manet (charcoal on paper, 1985; video 1975) and Self Portrait / Weeping Artist (pencil on paper, 1984-85).

Le Grice’s extraordinary career is laid bare in these works; an acknowledgement that an artist can be everything at once. Le Grice’s willingness to move from ‘traditional’ art techniques into experimental film and video, asserts the artist’s right to resist limitation. Le Grice’s self-actualisation galvanises the viewer; we never see the same artist twice, and the exhibition really serves a purpose in outlining not only the output of Le Grice’s career, but also its breadth.

In Self Portraits / Weeping Artist, Le Grice produces a series of tiny hand-drawn sketches. The repetition of the images, on first glance, echo Warhol’s iconic screen-prints. Reproducing the same image, each subtly altered, disrupts the grid-like pattern in which the portraits are placed. The neatness, like Warhol’s prints, is illusory. Look again, and the images begin to fragment. Le Grice also references Picasso’s Weeping Woman (1937). The nightmarish painting, an emblem of suffering, was itself part of a series, with Picasso revisiting the same theme several times over. With Le Grice’s portraits, the dismantling of the facial features is not so much homage but recognition of how art history informs contemporary artists. Picasso’s dissembled face is so ubiquitous it has become a type of shorthand; a rich vein to exploit in itself. Le Grice’s Self Portraits / Weeping Artist does this by subverting the male gaze so prevalent in the Picasso. Le Grice instead puts himself at the emotional centre of the piece, playing on pre-conceived notions of the artist and the viewer. The artist here is also the participant, and the viewer, by the act of looking, becomes part of the process too. It’s a theme Le Grice returns to many times in his work, most notably in his 1971 work Horror Film 1. Using three projectors, Le Grice films himself standing in front of the projection screen, arms outstretched. As Le Grice moves away from the screen, and towards the projectors, the distortions create shadows and blurring. The performer’s image is multiplied, as Le Grice’s role as performer and artist begins to merge.

Exhibition: Malcolm Le Grice Exhibition

After Leonardo

Plymouth Arts Centre Gallery, Lloyd Russell

In After Leonardo (triptych and installation), Le Grice creates a collage of the Mona Lisa image, interspersed with text from Sigmund Freud’s monograph ‘Leonardo Da Vinci: A Study in Psychosexuality’. Le Grice chooses his text carefully; the essay itself is a rarity, not freely available in book form in Britain since the 1930’s. It has now been made accessible – and been endlessly reproduced – in electronic PDF format. Le Grice displays a paperback copy of the text in a glass display case, along with a delicate, fragmented copy of the Mona Lisa head. Both are tattered and beyond repair, they are given the reverential treatment normally reserved for precious artefacts. On the wall behind the display case, a series of images are projected: snippets of text, fragments of Leonardo’s most famous work – that enigmatic portrait – is broken down into pieces, endlessly reproduced until nothing discernible is left. After Leonardo debates how meanings and theories are projected onto art, even the pieces where (you would think) everything has already been said. Le Grice’s work shows us how the meaning of art can alter with these readings. Freud’s analysis of Da Vinci remains ground-breaking. A reading of Da Vinci’s career without the inclusion of his sexuality, and how it coloured his work, is to read him with a piece of the puzzle missing.

Exhibition: Malcolm Le Grice Exhibition

After Leonardo

Plymouth Arts Centre Gallery, Lloyd Russell

However, Le Grice goes one step further and suggests that these readings are ultimately temporary. Despite the attempts to dismantle Da Vinci, (it has been suggested that the Mona Lisa is a portrait of the artist himself) our ability to understand him remains elusive. He / She is at once instantly recognisable – and utterly unknowable.

Le Grice’s After Manet (1975) is a 50-minute video that takes Edouard Manet’s painting Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe (1862) as its starting point. A piece of art with a unique place in art history, Manet’s painting of two clothed men having a picnic, accompanied by a nude woman looks, even to our eyes, strange and incongruous, and that is entirely the point. Manet’s juxtaposition of two elegant men-about-town and the classical female nude lifts the Impressionist painting out of any easily-identifiable context. All the signifiers are there, but they’ve been jumbled up to create a painting that plays with convention. Manet turned his back on the traditional modes of representation, and in the clamour by authorities to censor his painting (which unsurprisingly met with great scandal on its debut), Manet became one of the first modern art celebrities.

Manet’s work lends itself to reinterpretation, and Le Grice’s video borrows from the bold, questioning spirit of Manet’s painting to create a piece that is similarly disjointed. Filmed on four cameras, Le Grice had each camera operated by one of the actors appearing in the video; Annabel Nicholson, Gill Eatherley, Willian Raban and Le Grice himself. The artist becomes a performer, and the performers become stakeholders in creating the final piece. The performers recreate a picnic scene, and each person’s film is projected onto a screen, giving four views of the same subject. Switching from black and white, positive and negative, After Manet inverts the rituals of daily life; skimming through a book, drinking a glass of wine. It, like the painting, becomes otherworldly and unreal. Le Grice is well-known for his love of jazz music, and After Manet is a perfect example of how his art work riffs on established themes, in order to create something new. It is more than a reproduction; it is a new piece of art, with its own life. The piece then takes on its own history as it ages; meanings, readings – art viewed through a selective lens. Le Grice’s work, as viewed across this retrospective, admits that the temptation to grade and objectify is an impulse that is all too human. But maybe, suggests Le Grice, art should be more than the sum of its parts. This may be an exhibition of many moments, but in the end, there is one thought that binds them: perhaps there is no such thing as the last word, or final cut – and that’s just how it should be.

Helen Tope is a freelance blogger working and living in Plymouth.

@scholar1977

Comments

Comments are closed.