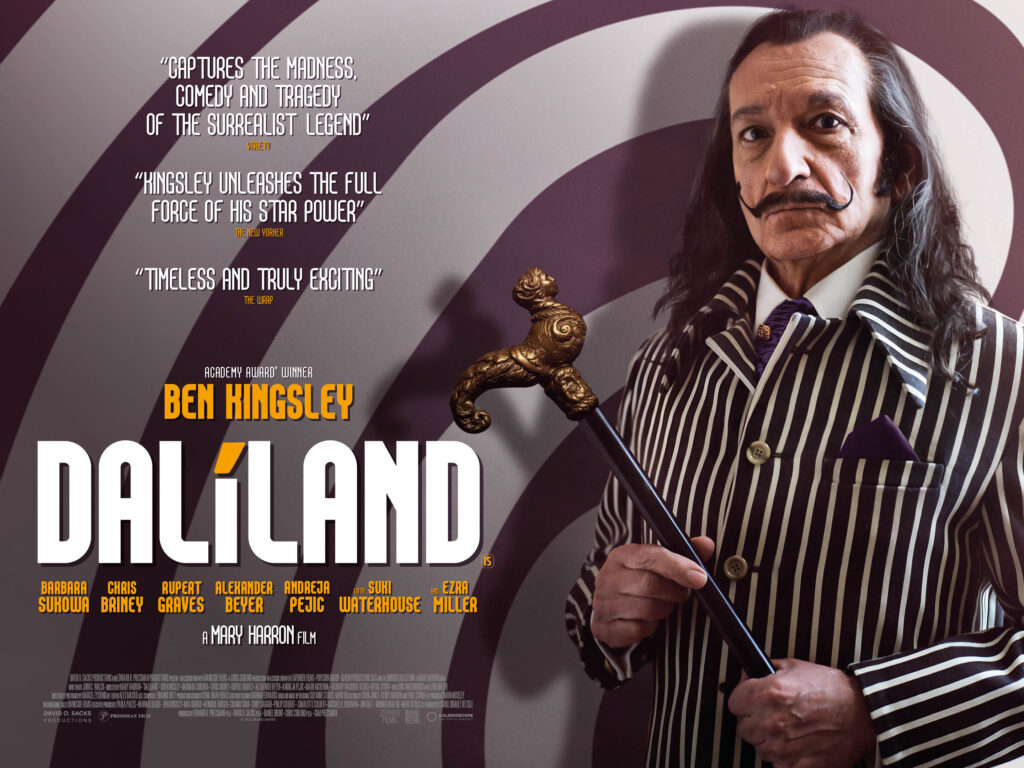

Trying to pin down the chaotic, surrealist world of Salvador Dali, Daliland is a biopic that doesn’t lack ambition. Directed by Mary Harron and scripted by John Walsh, this film explores the last decade of the artist’s life.

We enter Daliland from the perspective of gallery assistant, James (played by Christopher Briney). It is New York,1974, and his boss has asked him to deliver a suitcase stuffed with money to the St. Regent Hotel. This money is for Gala, Dali’s wife. A fearsome, intimidating presence, and in charge of the Dali finances, she only deals in cash. James enters the hotel suite and into a room packed with revellers, Dali is holding court. His next conceptual work, he boasts, will be to construct “the world’s biggest penis”. Dali is, of course, up against a deadline to fill the walls of James’ gallery with more sell-able prints and lithographs. James’ good looks not only get him through the door, he catches the eye of Dali muse, Ginesta (Suki Waterhouse) and the attention of Dali himself, who asks James to assist him through the next three weeks.

Dali is not only a cultural icon by this point, he’s big business. His prices are going through the roof, and demand for new work is hard to keep up with. The partying at the St. Regent is rightly legendary, but it’s throwing Dali off course. Harron takes us back in time to the beginnings of Dali’s most important paintings, and compares this period of productivity to where Dali is in later life: not out of ideas, but his inability to follow through is frustrating everyone around him. It also becomes clear to James there is an issue of quality control. Dali is signing anything put in front of him; prints sold at lithograph prices; photocopies passed off as the real thing. The man who prides himself on being an artistic enigma is churning out material that has little or nothing to do with original work.

In telling the story of an anarchic, eccentric artist, Daliland is far too reserved. Ezra Miller captures his spirit best, as the younger Dali, and it would be a different film if Harron had decided to lean into this era of his biography instead of the later years. Entranced by the full force of Gala’s personality, the younger Dali is bold, emotive and luminous with inspiration. By comparison, the time we spend with the older Dali lacks energy and drive. It’s all the more strange when we consider Harron’s back catalogue: American Psycho, I Shot Andy Warhol and The Notorious Bettie Page. These are films at full throttle; the idea that Dali has taken his foot off the accelerator is a neat metaphor, but it’s not enough to sustain the entire film. The scenes where we return to Dali’s youth, with the older artist looking on, have a sensitivity to them, but for the most part, Daliland is told in a fairly conventional structure, beginning and ending with the artist’s death in 1985. It’s questionable whether Daliland takes enough risks with its story-telling.

Another issue is the lack of biographical detail: we learn that Dali has a deeply problematic relationship with sex, but it’s never revealed why. A quick search on Google confirms that Dali’s introduction to sex was his father showing him explicit photos of people with advanced venereal disease; conflating sex, death and decay into one horrifying psychological moment for the young Dali. It’s a biographical note that explains both the art and the artist, but it’s missing from the film. It unfortunately gives Ben Kingsley, as Dali, very little to grasp onto. Kingsley skilfully portrays Dali’s changeable moods; the charismatic, confessional artist; and the near-hysterical hypochondriac. He relies on Harron’s close-ups to deliver much of his performance. The intensity of the eyes draw you in; Kingsley’s Dali is forever searching and analysing.

There are further bright spots: Barbara Sukowa’s Gala is excellent; Mark McKenna and Zachary Nachbar-Seckel have great fun with their cameos as Alice Cooper and Jeff Fenholt. Harron does capture an essence of the Seventies. The gathering of artists and muses in the sweet spot where bohemia meets opulence; great tunes, even better clothes and hard drugs served on a silver platter. The preservation of glamour, staving off the visible signs of old age, becomes more poignant as the film progresses. As Dali’s hand betrays a tell-tale tremor, the confirmation that death cannot be held at bay forever, genuinely frightens him. It is fear that motivates the golden couple: Gala’s terror of returning to poverty sees her wailing about being poor while standing in a hotel suite costing $20,000 a month. Daliland illustrates the tensions in being not just an artist, but a bankable name. A gallery owner whispers to a buyer that Dali’s prices have increased ten-fold: people are buying his work as an investment. Dali’s still producing work worth talking about, but the critical response is muted: his lifestyle and celebrity have overshadowed the creativity. Despite the high prices, what Dali makes never seems to be enough: the cost of living at Casa Dali is giddying.

Daliland nudges us into asking questions about authenticity, but it is the multiplicity of Dali: that provokes: among the characters and ploys, is there even a real Dali? It’s a debate that is, appropriately, never resolved. Even James’ relationship with the artist is thrown into doubt, nothing is quite what it seems. This final, uneasy note is finely-judged; Harron and Walsh avoid the temptation of a rounder, neater ending. No matter how close we did – or didn’t get – to Dali, there’s always another layer to peel away. The artist, and the man, remain at large.

Daliland is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema from 20th – 26th October

Reviewed by Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.