The SAFAR Film Festival is the largest Arab film festival in the UK and was set up in 2012 by the Arab British Centre. This year, Plymouth Arts Cinema had the pleasure of being one of the screening partners.

Running from 29th June to 9th July across the country, a plethora of films and documentaries were shown, highlighting both the beauty and the turmoil in the past, present and future of the Arab speaking world. Each year has a specific theme which the selected films centre around, and this year’s was ‘A Journey through Space and Time’. There are several sub-topics that are highlighted in this year’s festival, as it is the 75th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba, where the forced deportation of Palestinian nationals began following the formation of the State of Israel. There is also a country focus on Morocco, as well, as several UK premieres. Partnered with many Q&As and talks by everyone from directors to local CICs who work with these communities, this rich festival was a definite hit.

At Plymouth Arts Cinema, the journey started with Tunisian film Ashkal, which you can find a review of on the PAC blog.

On 6th July, there was an evening celebrating food and defiance. It began with a 2006 short film by Larissa Sansour, entitled Soup Over Bethlehem. As the name suggests, the entire nine minutes are of a conversation between Sansour’s family whilst eating various traditional Palestinian dishes on their rooftop overlooking Bethlehem. They begin by discussing the food itself and how to cook it, but the conversation turns quickly to the general unease in the country. This was filmed as the West Bank Barrier is being finished, which had an inordinate negative impact on the movements and freedoms of Palestinians. The film is in grayscale, apart from the food, a technique used by Sansour to ensure her audience focus on what she wants them to.

This was followed by the feature length Foragers, which focuses on Palestinians who forage essential cooking plants for themselves and their loved ones, despite the bans put upon them by the Israeli State. Although plants and herbs such as za’atar have been harvested in the wild by Palestinians for centuries, Israel has made them a protected species, meaning that those who do pick them face hefty fines if they are caught by the authorities. In the film, we see a forager being given a fine of 700 shekels for a first offence (around £140), which is clearly an inflated figure for the severity of the crime. In some archival news footage from the 1970s, we hear Israeli businessmen discussing how they are going to phase out wild za’atar, and make the market exist solely of cultivated za’atar, therefore forcing Palestinians to pay them in order to obtain a food that grows wild on their land. Nevertheless, foraging is still common, showing the pride and determination of the Palestinian people, who often become ‘dealers’ of these precious ingredients.

This was accompanied with a talk by Cathi Pawson, co-founder of Zaytoun (meaning olives), a CIC which supports Palestinian farmers in distributing their produce in shops such as Oxfam. 100% of their profits are reinvested into helping achieve this fairtrade mission. They also organise annual trips to help their farmers bring in their harvests and sell their produce. She spoke about the ever-increasing issues for their trips in going out to Palestine, but also of the joy in helping this cause. There were also some sampling plates of bread, olive oil and za’atar for the audience to taste, all from Zaytoun, which was a lovely end to an informative evening.

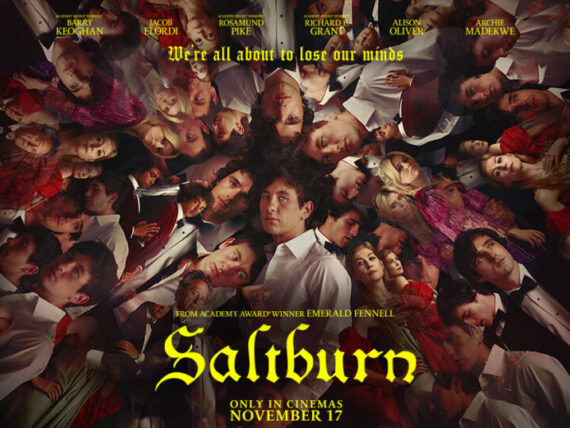

Rounding out the SAFAR films in Plymouth was a love story of both love and lust. Set in the coastal Moroccan city of Salé, The Blue Caftan is the tale of Mina and Halim, who own a caftan boutique in the city’s medina. Due to the small size of their workforce, they are forced to take on an apprentice to keep up with orders. Halim is adamant that he will not use a machine, and this dedication to a craft is something subtly peppered throughout the film. Although Halim is confident their apprentice Youssef will stay on with them and become a caftan craftsman, Mina is less confident. She argues with Halim that the craft is dying out, and that there is nothing he can do about it.

However, this is mainly a film about love in all its forms. It is clear from the moment Youssef enters the shop that there is some tension between him and Halim, although the latter tries to suppress his desires. His sole outlet for his homosexuality is in the individual booths at the public baths. However, it is still clear that he deeply loves Mina, as well as being attracted to Youssef. As Mina becomes more and more ill throughout the film, he shows his love to her by constantly caring for her, to the detriment of customers.

I am sure this film will have resonated with those who have ever cared for a loved one, and those who have ever needed to hide a part of themselves, whether for religious, cultural, or political reasons.

Reviewed by Imogen Parkin

Comments

No comment yet.