A glorious, whimsical love letter, the French film Amélie sets its heart on convincing the cynics among us that romance – real, honest-to-goodness romance – is still very much alive in the 21st century.

Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Amélie is introduced to us in montage. She lives an isolated childhood with her unhappy parents, and when she leaves home, she buries herself in a waitressing job in a Parisian cafe. But Amélie (a star-making role for Audrey Tautou) is filled with curiosity: she notices everything around her. She makes a chance discovery at her flat, when she unearths a tin box, filled with a boy’s keepsakes from decades before. She asks around: her concierge, her grocer – do they know the name of a boy who lived in her flat during the 1950’s? A twist of fate leads her to the correct person. She engineers a situation in which the man finds the little box seemingly by chance. As the anonymous benefactor, she watches him transform: Jeunet floods the screen with black and white images as the box’s contents bring back childhood memories. The nostalgia ignites in him a desire to reconnect with his estranged daughter. He has not even met his grandson.

Amélie, giddy with her first success, develops a taste for improving people’s lives. She imagines a life spent in the pursuit of happiness for others. Jeunet recreates a televised, lavish funeral for elderly Amélie, “the godmother of outcasts”. In a bid to jolt her widowed father into moving on, she mischievously steals his prized garden gnome who sends back polaroids of his globe-trotting voyages. She also spots potential for romance in her workplace, matching a customer with the girl who works on the cigarette stand. If you’re thinking this plot sounds vaguely familiar, there is definitely a touch of Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse in the Parisian Amélie. Both heroines have a day of reckoning, but it isn’t until Amélie discovers a strange photo album – filled with ripped and discarded photo booth strips – that she examines her own life, and begins to realise that she is also lonely. The photo album, owned by local boy Nino (Matthieu Kassovitz), is the key to Amélie’s happiness. But will she grasp the opportunity for a new life?

On its release in 2001, Amélie was a massive hit at the French box office, but elsewhere, critical reception was divided. The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw referred to the film as “gooey”, but Roger Ebert dubbed it an “absolute masterpiece”. Over 20 years later, it is the style of Amélie that endures. Jeunet’s sepia toned magic realism – talking photos, a Dali-esque Amélie melting into water – has resulted in the visual language of Amélie becoming more famous than the film itself. The surrealist touches lend themselves effortlessly to the world of memes and GIFs. The shot of Amélie with a spoon, ready to crack the glaze on a crème brulee, is so well-used, you would be forgiven for thinking Amélie is a foodie film, if you had never seen it.

Rewatching it now, the style of the film still what demands the lion’s share of our attention. Jeunet, despite anchoring the film in the days following the car crash that killed Princess Diana, locates Amélie in a richly-imagined Parisian Golden Age, where elements of the modern day rub shoulders with a playground of nostalgia. While Amélie works in a beautifully-preserved 1950’s cafe, Nino does part-time retail in Porno Palace. Grocers sell fruit and veg on street corners, but good luck finding a Big Mac.

This dissonance within Amélie is perhaps less jarring to us now, than it was in 2001. Films like Amélie introduced more adventurous fare to cinema-goers raised on a diet of films with an Anglo-American sensibility. Our continuing eagerness to explore the worlds of Pan’s Labyrinth, Spirited Away, Roma and Parasite indicates the appetite for global cinema is not a shrinking trend. Thanks to the proliferation of social media, we can also see foreign films as part of the bigger picture. Michelle Yeoh’s stirring Oscar speech did the rounds on TikTok and Instagram. Who will win the Cannes Palme D’or is hotly debated on Twitter. When Amélie was released, the launch of Facebook was still three years away.

But as Amélie has aged, its central concern, that “times are bad for dreamers”, feels more universal as we negotiate our way through a post-pandemic malaise. This Parisian fairytale, with its homage to the creative world, nudges us towards optimism. Travel, art, love – whether it turns sour or not – the point is to just dive in. The emphasis on building connections is what ultimately earns Amélie its modern classic status. The film that is outwardly sentimental sees the future with crystal-clear vision. Its sense of joie de vivre is still as bracing, and as fresh.

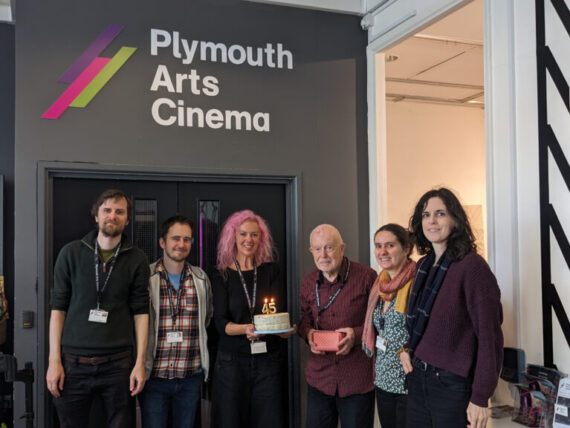

Amélie is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema at 5pm on Saturday 3rd June, followed by live music with A Journey into French Music at 8pm.

by Helen Tope

Comments

No comment yet.