I first saw Raging Bull in the early nineties, on an actual black-and-white TV (so I missed the occasional spurt of colour within it). Its director Martin Scorsese had revamped the gangster genre a year or two before with Goodfellas, an eye-popping, fast-cutting, amphetamine crush of ultraviolence, seemingly made for a generation weaned on MTV through the eighties.

Raging Bull, made a decade earlier, was noticeably much steadier and deliberately paced. It took its time to examine its subject, inside and outside the boxing ring, even (especially?) when his behaviour is unbearably and unflinchingly ugly.

That subject is of course Jake La Motta, with his real-life, rag-to-riches-to-rags story of a pug-faced middleweight fresh out the post-war Bronx, here portrayed with mesmerising charmlessness by Robert De Niro. He’s kept in check, up to a point, by his long-suffering manager Joey (an excellent Joe Pesci), who has to deal with the competing desires of his brother to be champ, and the petty crooks who surround them and want to see him sacrificed for a fast buck.

Their tale is almost too much of an old saw to be true, about the kid who fought all the way up to be world champion, only to slide down the other side just as readily, skidding towards low-life criminality and nightclub sleazedom. It’s a story that’s passed so far into movie folklore it’s nearly become a cliché – I say nearly, because Scorsese always remains a knight’s move away from La Motta, never getting too close to his subject or allowing him to become sentimentalised.

The fight scenes remain exhilarating as ever, in particular match after match against his nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson. The pounding of sweat off their faces sprays onto the ringside seats so vividly it feels like we’re getting an eyeful ourselves as well. (Cinematographer Michael Chapman surely deserves all the praise he gets for his work here.)

La Motta’s life outside the ring was also saturated with violence of all kinds, most grievously shown towards his family, particularly his second wife Vickie (Cathy Moriarty). The actual violence he ends up unleashing arrives only after years and years of mental torment he put her through, and we are spared neither in this portrayal of a brutal and ultimately unlikeable man.

The film contains a postscript, a quote from the Bible, ending with a cured sinner exclaiming, “I was blind, but now I can see.” This is curious to say the least, because it is not altogether clear how less of a blind man La Motta is at the end of it all than he was at the beginning. What Scorsese does seem keen to show, however, is the degree to which those champions we are so eager to get behind may just be sinners after all, and he does this incredibly powerfully.

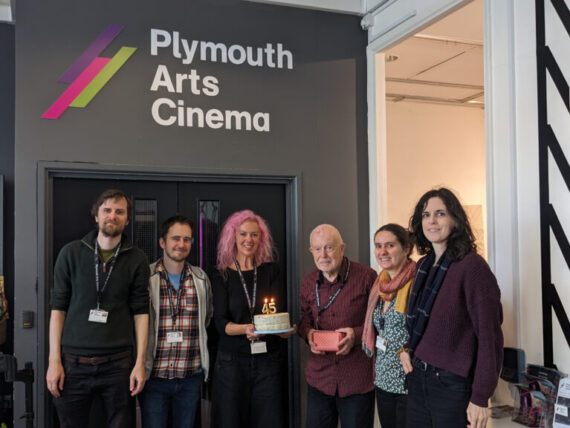

Raging Bull is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema from Saturday 22 – Wednesday 26 April. The screening on Tuesday 25 April will include an introduction by Dr Eddie Falvey, lecturer at Arts University Plymouth, as part of the Screen Talk series.

Reviewed by Ieuan Jones

Comments

No comment yet.