Starting with a premise, Women Talking presents us with a single phrase: “What follows is an act of female imagination”.

Taken from the novel by Miriam Toews, director and screenwriter Sarah Polley adapts a story of an isolated religious community (they refer to themselves as a colony), with a dangerous undercurrent of abuse and violence, meted out to the women and children of the group. The phrase “female imagination” refers to the Elders’ attempts to dismiss acts of sexual abuse. The community structure is densely patriarchal; the women receive no education and subordination is expected. With the attacks, we observe a pattern: the women are secretly drugged and wake up the next morning to find themselves bloody and bruised. The Elders refute that the abuse is from within the colony. They suggest instead that the attacks are the work of Satan. When one of the attackers is nearly caught (and identified) by the women, he is taken to a local police station for his own safety. The men of the colony head into town with him, leaving the women alone. It is here that they have space, an opportunity, to discuss what happens next.

The women gather in the courtroom-like space of a hayloft. Before them are three options. Do nothing. Stay and fight. Leave. This is not a simple case of self-preservation: their decision is more complicated, as leaving the colony will result in them being ostracised from their community and their faith. Some state their position early on. Scarface Janz (played by Frances McDormand) declares she will remain. A hook-shaped dent in her cheek silently bears witness to the trauma she has experienced. The women have asked August, the school teacher (Ben Whishaw), who has remained behind, to take notes. He is a quiet, respectful presence – a rare example among his male counterparts. The only member of the colony to have left and come back – he received a university education in his time outside – August is given the task of listing pros and cons for each option.

A vote – the women mark their intent with an ‘X’ – proves inconclusive. They begin to break down what each option will mean for them. The younger women, Salome (Claire Foy) and Ona (Rooney Mara), ponder the issue of forgiveness. Left pregnant after her attack, Ona asks whether forgiveness is true forgiveness if it is forced. The lines between forgiveness and permission are blurred, understandably, as they have been for some time.

Polley’s script cleverly layers ideas: this is as much philosophical exercise as it is a race against time. There is an urgency that pushes the women to act with impunity. Collected in one space, speaking freely, it becomes clear that the years of abuse these women have endured have left an indelible mark. Mariche (Jessie Buckley) sits hunched, visibly tensed; her demeanour evoking the terror of a hunted animal. She scoffs at Mejal’s panic attacks as she experiences flashbacks of her rape. A terrific performance by Michelle McLeod, Mejal is spirited and not afraid to ask awkward questions. The women may be physically exhausted, but their minds are eagerly grasping at, and picking apart, thoughts about life, the afterlife, and whether one should be sacrificed for the other.

Women Talking is very much an ensemble piece: we have the wide-eyed dreaminess of Ona, and the fierce, maternal rage that seeps out of Salome as we learn her 4-year-old has been one of the victims. The debate isn’t steered by one person, but the sagacity of widowed Agata (Judith Ivey) provides moments of relief. The job of narration also jumps between several characters, but most poignant, is the singular voice of Mariche’s daughter, Autje (Kate Hallett). She whispers, conspiratorially, to Ona’s unborn child. There is not just the present to consider, but the future.

The colony’s sense of separation (only broken briefly by a census van circling their perimeters, asking them to come out and be counted), feels otherworldly, until you consider that Toews’ novel is based on real-life events. The revelation of abuse within a Mennonite community in Bolivia made headline news in 2009, and darkly echoes the content of the film. The flashbacks are deliberately shot in black and white: memories frozen in time. The attempt by the Elders to silence the women; to make them disbelieve their own experiences, becomes the impetus for change. Things cannot go on as they are. Two options remain.

Polley’s measured, empathetic depiction of a closed community plays on our prejudices. In detangling this argument, there is clarity of thought and wit. The women continue to talk. This may represent a profound test of faith for them, but Polley never lets us forget what has brought them to this point. At the centre of the film, there is a deep, unresolved anger.

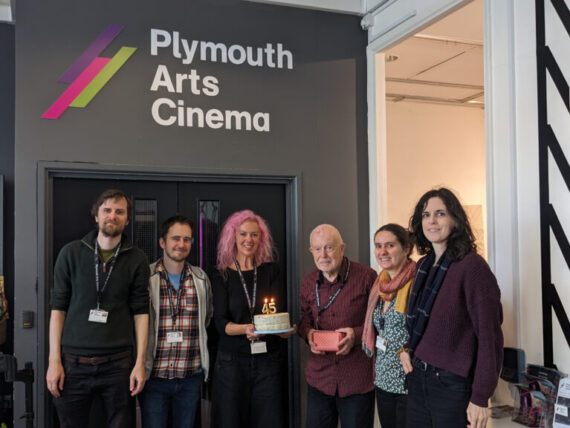

Women Talking is screening at Plymouth Arts Cinema from Friday 3 – Wednesday 8 March.

Reviewed by Helen Tope @scholar1977

Comments

No comment yet.