Art Review: Katya Sander – Publicness

Katya Sander’s Publicness is showing at Plymouth Arts Centre from 1 September – 29 October. Helen Tope reviews the exhibition.

Publicness is an exhibition that takes stock of Katya Sander’s career to date, with many of the pieces revisited and recreated by Sander especially for Plymouth Arts Centre. It lends the exhibition an immediacy that is sometimes lacking in traditionally-staged retrospectives, giving Sander’s ideas a freshness and vivacity.

Born in 1970, Katya Sander lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin. Sander balances an impressive academic career with a busy exhibition schedule. Most recently showing in solo exhibitions at Tate Modern and MOMA, Sander’s work has travelled the world.

Indeed, in reviewing the details of Katya’s career, it becomes clear is just how much of her work is shown internationally. In an essay on the Danish contemporary art scene, critic Lisbeth Bonde discusses how ‘pluralistic’ young Danish artists’ work has become. Through the support of organisations such as the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and the Danish Art Council, artists are encouraged to network – not just across Europe, but showing their work in creative hubs such as New York and Tokyo. As a result, Danish artists are creating work that speaks many languages. The Danish art scene itself has undergone a ‘golden age’ over the past 15 years, with artists such as Tal R, Elmgreen & Dragset and Olafur Eliasson building an international reputation.

Working in a variety of mediums, Sander’s work takes on a restless, roaming quality. The mind is never quiet – but always searching, always asking. Having participated in group and solo exhibitions, Sander has developed a singular voice. Questioning societal structures, patterns, obligations – and our place within them – Sander creates work beyond nationality. The work is everywhere and nowhere at the same time, and it soaks up influence from wherever it has been displayed. Sander’s work never stays still for too long – it is the consummate traveller and needs no translation.

There is a strong DIY aesthetic throughout the exhibition, with the production of the artwork (excepting the videos) taking place on-site. This gives a personalised, improvised quality to the exhibits. Sander’s choice to work quickly and within set contexts gives the artwork real specificity. Talking about her work at Plymouth Arts Centre earlier this month, Sander remarked that she tends to focus on ‘nerdy’ details – and it is the absolute focus on a question, or a supposition, that makes her work so individual.

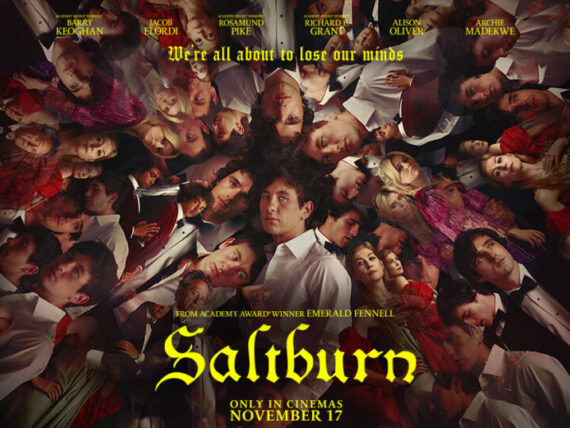

The exhibition takes in several pieces from Sander’s career so far, and one of the most accessible pieces (especially for film buffs) is The 100 Most Watched. Originally created in 1998, the artwork is based on IMDB’s list of films in order of their global ticket sales. Painted in bold black letters on the ground floor wall, the graffiti-style, rambling narrative is allowed to drip and run into the line below it.

For this exhibition, Sander has gone back to the list and updated her artwork – which is why we see films such as Avatar (2009), next to films such as Star Wars and Titanic, which would have been featured in the original.

In looking at the box-office appeal of Hollywood’s leading men, Sander decides to investigate the power of the narrative by inverting the gender roles in each film, meaning that every male character becomes female, and vice versa. By taking the films out of their original context, Sander re-tells familiar stories. Not only does the narrative seem to change, but how we read it appears to change also. It neatly explores how we graft certain personality traits onto gender (bravery, heroism, a sense of adventure = must be male). Located next to the Arts Centre cinema, it’s a great, thought-provoking piece and the perfect place to start exploring the exhibition.

Sander’s work stretches over several mediums, from light, quick sketches to edited film. In the first of two videos featured in the exhibition, Exterior City (2005) shows a woman putting up posters – ‘a manuscript’ she calls it in one scene – around a city. The posters are lists of names – addressing groups such as ‘Dear workers, bosses, tenants, landlords…”

Sander presents this city as an imagined state – sat ideologically somewhere between Vienna and Malmo (Sweden’s third largest city). Sander’s references are deliberate – both Sweden and Vienna have a long history of providing social housing. For Sander, it raises questions around what happens when the residential (personal) and political coincide.

In a group exhibition Home Sweet Home (Sweden, 2011) Sander’s contribution was a lecture titled ‘The usefulness of inadequate models’. In the lecture, Sander discusses how social dictations are created by society, and in turn how they influence individual thoughts and actions. In Exterior City, Sander creates a tension between real and staged actions. The woman in the video often looks off-camera, questioning where she should go next. Interspersed with this are real interactions between the woman and people who see her putting up the posters. Some ask questions, others simply read the poster as she tapes it up. When asked by one of the bystanders if she is acting, the woman replies that the process of putting up the posters is an act. The bystander pretends to understand and walks away.

What I found particularly interesting, and it’s a thread running through many of Sander’s works, is just how vocal the pieces are. Words are everywhere in this exhibition – written and spoken. Rather than dictating terms, I found that the constant presence of words and sentences provoked me to ask questions. In Exterior City, there are subtitles: some reflect what is literally being said, others provide commentary on what is implied by the action on-screen.

The video’s narration jumps about, from 1st person to 3rd person, with male and female narrators. ‘I’ moves to ‘she’ with alarming ease; “She imagines a catastrophe”. Sander keeps the viewer engaged with questions, spoken or inferred. It is a singular motif that you can identify in the works featured in the Publicness exhibition. Sander questions the politicisation of architecture and our place within it, and as we move through the exhibition, it becomes evident that Sander’s interests move between the political and the individual, producing work that questions the social constructs we take for granted.

You can see in this exhibition how Sander’s exploration of social constructs is informed by her interest in commerce. In Statements in Relation to a Bank, Sander fills an entire wall with rainbow blocks of colour. Handwritten across those blocks of colour are excerpts from interviews Sander held with investment bankers.

The original piece was produced in 2008 in collaboration with Nykredit, one of Denmark’s largest banks. Sander gained access to this world by asking unexpected questions as a ‘way in’ (eg: asking during a tour of a bank’s premises, if she could touch the server) It was an attempt to throw the interviewees off-guard, to get beyond the well-practised, corporate patter.

The excerpts from the interviews, taken out of context, become highly revealing – Sander’s attempt to throw the bankers off-balance makes for interesting reading. The colour blue, we learn, is a shade favoured for outlining corporate identity in the banking world – quite literally “blue-chip”. One interviewee reveals that Pantone 280 is their institution’s corporate shade – a very sober shade of blue. They talk a lot about imbuing trust in their customers, their clients. Is blue an honest colour? Barclays certainly seem to think so.

Statements in Relation to a Bank plays with colour – its moods, tones and associations. As the questions get more serious, the handwriting strays into the more playful shades – pinks and yellows. The insecurity of the finance world is written on the wall for all to see. Sander asks about the physicality of this world? How solid is a banknote? Why is it considered more ‘real’ than numbers on a screen?

Servers are now storing information – huge servers – so money (even as electronic data) is taking up more physical space than ever before. But even this vastness is transitory –it will be replaced by another technology in time, and the servers will be defunct. The shuffling of numbers on a screen – profit and loss– is at once enormous and ephemeral. With the jargon tailored to the banking world, Sander illustrates how the people working within the system are literally speaking a different language.

In order to engage with the interviewees, Katya had to learn the lingo (words such as ‘derivatives’ and ‘futures’ have very specific meanings in the finance world). Definitions of these terms can be found on websites such as Investopedia – and just glancing through this website gives an insight into how differently the world is viewed through this particular lens. It’s both fascinating and unnerving, and I think this is why I found this piece to strike most clearly at the heart of Katya’s work.

Created just before the advent of the global financial crisis in 2008, this piece now, by necessity, is read differently. We cannot help but project experience onto it – and the tone changes. Gentle inquisitions take on a darker hue. Our value is a number on a screen, and it is this idea that Sander explores further in Financialisation.

It is a video taken from an earlier work where Sander interviewed statistician Emmanuel Didier about the role statistics have to play in the global financial markets. Here, Sander gives us the footage of the full interview with Didier.

In Financialisation, Sander muses on our relationship to money: how we ourselves are both debt and risk. Through student loans, credit cards, mortgages, we assimilate debt and through that debt, we become risk. A bank buys multiple high-risk debts and that risk then becomes diffused – any impact through loss becomes minimised. In this context, a person becomes merely a calculation of loss and risk – you are a standardised fragment of yourself.

Financialisation is one of the most open-ended pieces in the Publicness exhibition – it touches on many of the themes that have influenced Katya’s career. How notions of value, commerce and identity exist within a collective subconscious. It’s a space without limits and boundaries, as it’s constantly shifting and evolving. Publicness may be a summary of where Sander is now, but it’s clear from this exhibition that there will always more to examine.

While retrospectives remain highly popular with art galleries, exhibitions featuring mid-career reviews seem far thinner on the ground, and yet with Publicness, there’s a compelling case to be made for them.

What ties this collection together is how work changes over time. Even when created in a very specific context, we see here that artwork continues to evolve and adapt, because we imprint our experiences and thoughts onto it. Sander’s exploration of the financial world not only highlights its separateness, but its tendency to dehumanise. Learning that we are considered statistical fragments isn’t too much of a surprise, but it also explains why the financial markets are so eager to take risks. It’s a high-stakes game where the consequences are shouldered by someone else. The pain is deferred, and the game plays on.

It’s this dehumanising that Sander seems to be rallying against in much of her work. The hand-crafted, improvised technique that goes into creating many of her pieces, is a refreshing antidote to the glossy, industrialised productions associated with contemporary art. Her hand is visible in all of this work, and it makes the exhibition an intensely personal experience. Nothing is perfect in Sander’s world; the raw edges – physically and metaphorically – add to the sense that Katya is always revising, revisiting. Nothing is finished, and that’s entirely the point. No work is complete because its meanings will change and adapt as the world moves on. New obsessions and talking points will reveal themselves. In Publicness, art is never done. The artist looks back, then forward – and the work continues.

Helen Tope

Twitter: Scholar1977

Comments

No comment yet.